For Black History Month, the gar spot will focus on a handful of the many gifted and talented black women instrumentalist who play jazz.

Many can easily rattle off a list of some of the biggest names from the Swing Era. Count Basie. Duke Ellington. Fletcher Henderson. Benny Goodman. Artie Shaw. Lionel Hampton. But one of the biggest names of the period rarely appears on most big band lists. Indeed, many folks have never heard of them.

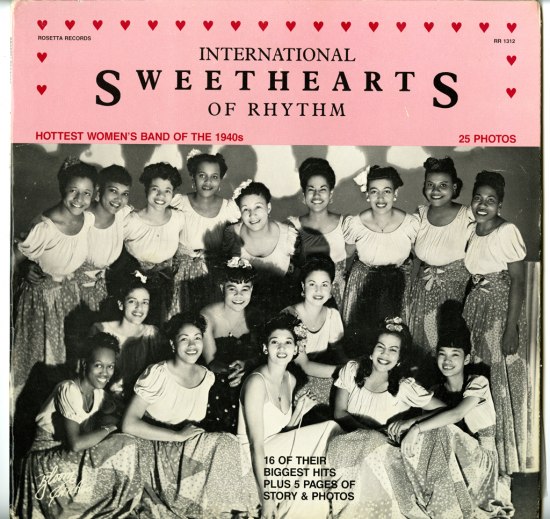

The International Sweethearts of Rhythm was one of the most successful all-women bands from the Swing Era and one of the biggest names in the business. At their height, they packed venues and sent folks into a Lindy hop ecstasy.

The group started as a bunch of kids playing music together: Evelyn McGee, vocals, Pauline Braddy, drums, Willie Mae Wong, baritone sax, Irene Grisham, tenor sax, Ione Grisham, alto sax, Johnnie Mae Rice, piano, and Helen Jones, trombone. They all attended the Piney Woods Country Life School in Mississippi. The school’s founder, Dr. Laurence C. Jones, Helen’s father, encouraged the young musicians to start playing swing. The group played at school functions and locally, then later, as their acclaim grew, they began playing regionally.

By 1941, the International Sweethearts of Rhythm adopted their famous name, expanded to 17 members, and set out on their own. A multiracial group featuring Asian-American, Latina-American, Native American, as well as African-American and white musicians, they mostly played in black venues from Central Avenue clubs in Los Angeles to the Apollo Theater in Harlem. Audiences loved them and quickly learned that they were not just a novelty act, but serious musicians with hella chops. They knew the music and swung it hard. Newspapers gave them glowing reviews, though usually with the “compliment” that they played “just like men.”

They traveled the country by bus, including into the Deep South. Pianist and bandleader Earl Fatha Hines would later call the Sweethearts “the first Freedom Riders.” When Duke Ellington took his first trip to the South, he hired a railway car for the band to travel and lodge in, so that they could avoid the indignities of Jim Crow. Similarly, the Sweethearts stayed on a custom-built sleeper bus—built by members of the Piney Woods school. No hotels would put them up nor would restaurants serve the multiracial group. White members, like saxophonist Rosalind Cron, learned that she would be treated like her bandmates of color—refused service at restaurants and the like—if she stayed with them. She chose to stay with the Sweethearts.

During an interview session at the Smithsonian in 2011 with some surviving members of the Sweethearts, one of the musicians recalled that they received more respect from black musicians than from white ones. The white boys ignored them, she said. In general, the Sweethearts were better known in the black community than the white community. As noted, they tended to play in black owned and operated clubs. However, in 1945, the Sweethearts went to Europe and played for the troops, black and white, in France and Germany.

The International Sweethearts of Rhythm lasted through the swing era, breaking up in 1949. Most big bands broke up by that time. Musical tastes had migrated from large jazz ensembles to small rhythm and blues and later rock and roll groups. Jazz similarly turned towards smaller groups, playing bebop and by the 50s hard bop. And despite the Sweethearts’ popularity during their active years, once gone they fell into obscurity. Only starting in the Women’s Rights movement of the 60s and 70s did they enjoy a resurgence of interest into their music and history.

Not many of the Sweethearts’ recordings survive. But here is a Best Of album available on Spotify.

Here is video of them playing on the bandstand:

© 2019, gar. All rights reserved.