When the Cassini probe launched in 1997, some controversy followed it for the first part of its voyage. Probes heading to the outer solar system need a speed boost. Big chemical rockets are too impractical and expensive. Ion rockets, though promising, can’t provide the power needed at this time. So for decades, rocket scientists have used gravity boosts from planets. They slingshot a craft around a planet, and it comes out the other side going quite a bit faster. A unique alignment of the planets allowed the Voyager probes to slingshot their way all the way to Neptune and beyond.

For the start of its mission, then, Cassini slingshot around Venus twice and then the Earth once. It was the Earth slingshot that got it into trouble. Cassini, like all deep space probes, derives its electrical power from radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs). It had three. Solar arrays, like those at the International Space Station and probes orbiting Venus or Mars, were not practical at the time of Cassini’s construction. The Juno probe, currently orbiting Jupiter, does have solar arrays, the technology having advanced to where this is possible.

But Cassini had to do it old school. And when folks found out that it was about to buzz past the Earth, panic struck. What if it crashed into the atmosphere? Where would it hit? Who would get harmed by it? Would it go off like a thermonuclear device?

Well, no. The greatest risk of contamination from the RTGs was during launch. It thankfully survived its launch. By the time the craft came back for a flyby, the risk of an accident plummeted to 1 in 1,000,000. I remember writing to NASA in support of the probe and its mission. Someone sent back a very appreciative note with pictures. (This was back in the snail-mail days.)

But all of that is long ago and largely forgotten. By the time you read this, Cassini will have finished its historic 13-year run orbiting Saturn and crashed into the Ringed World. It’s a protective measure, the controlled crash. While spacecrafts undergo stringent decontamination procedures, there is still enough of a chance that a craft may carry terrestrial microbes that scientists prefer not to take any chances. Rather than risk contaminating one of Saturn’s fascinating moons, some of which may harbor its own indigenous life, they will sacrifice the probe.

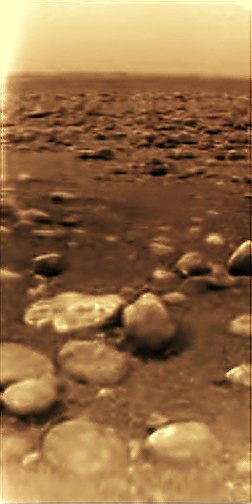

I’m rather saddened by this. By any measure, the Cassini-Huygens missions has been one of NASA’s greatest success stories. When it arrived in 2004, Cassini sent off the Huygens probe for Titan. It cruised through the thick atmosphere of the giant moon and then successfully soft-landed on its surface, the first time a probe has landed on a moon other than Earth’s. It survived this harsh environment long enough to send photos from the surface, another first.

Saturn has a collection of wonderfully weird moons. Cassini’s first port-of-call was the moon Phoebe (FEE-bee), one of the outer most moons.

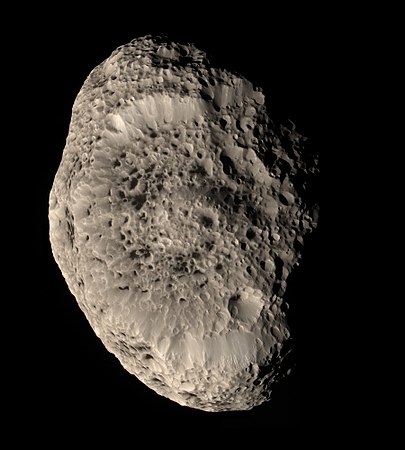

Hyperion looks just plain bizarre, like a sponge.

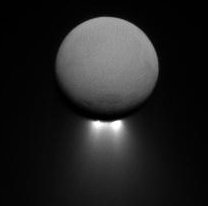

And Enceladus surprised everyone with its “tiger stripes” that spout geysers high into space. Turns out that Enceladus has water under its smooth, icy surface, a vast ocean.

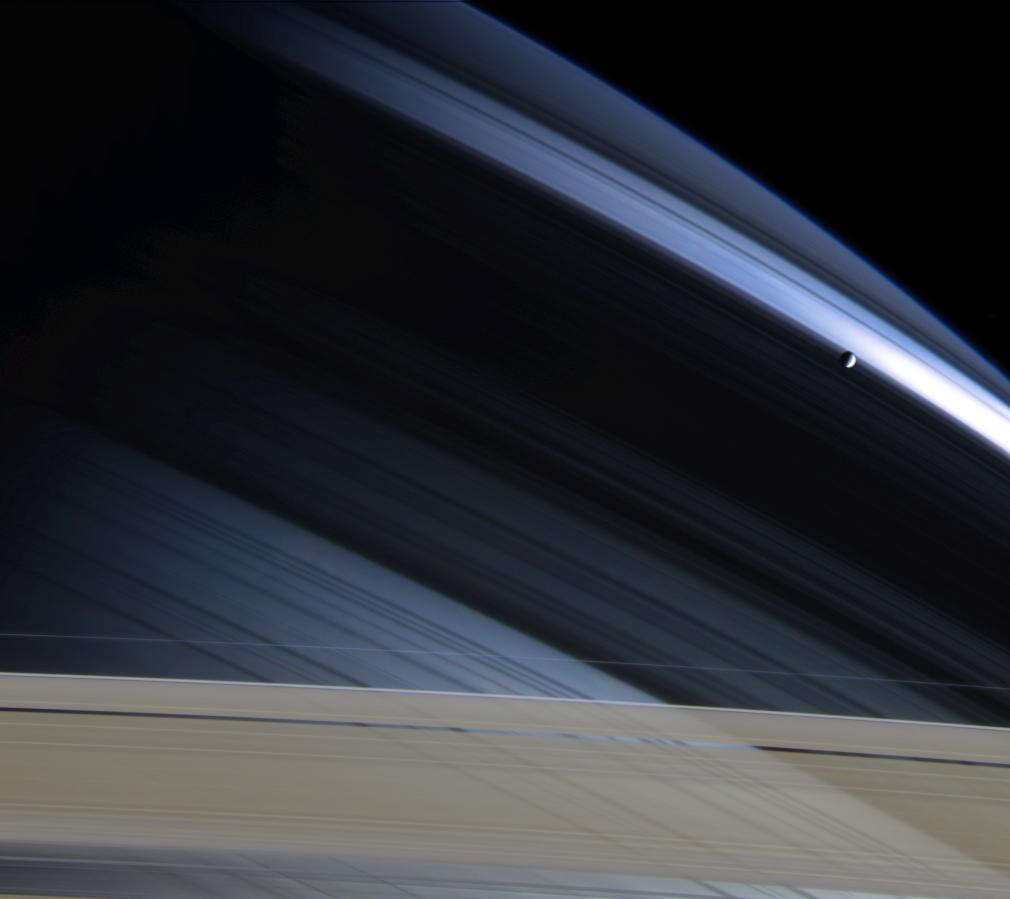

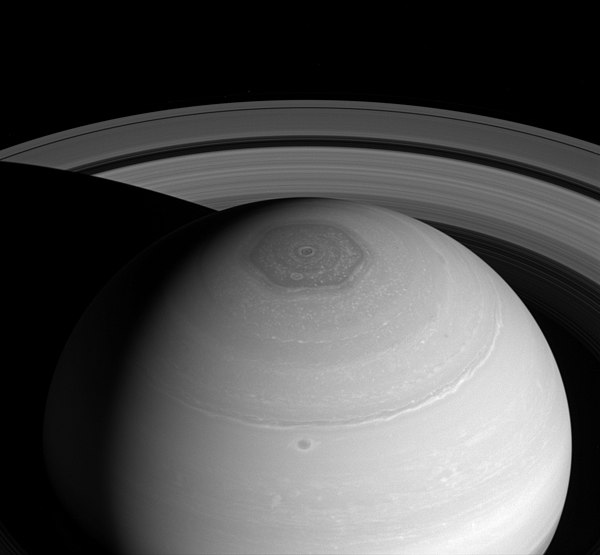

Of course, when talking Saturn, one has to talk about the rings. Cassini showed them off in the most fascinating light possible. For thirteen years, we received photos like this:

Saturn itself provided endless fascination, with its turbulent, storm-ridden atmosphere. It has hexagon-shaped jets at its polar latitudes, along with large, permanent hurricanes. It has storms and lightening. These features have fascinated the space-watching public and enthralled planetary scientists.

Thirteen years is just a few years shy of half a year on Saturn. Thus, Cassini observed seasonal changes. The blue hues over the northern hemisphere moved south over the course of the mission. I’ve never seen such gorgeous space photos before. How wonderful that we received a treasure trove of them.

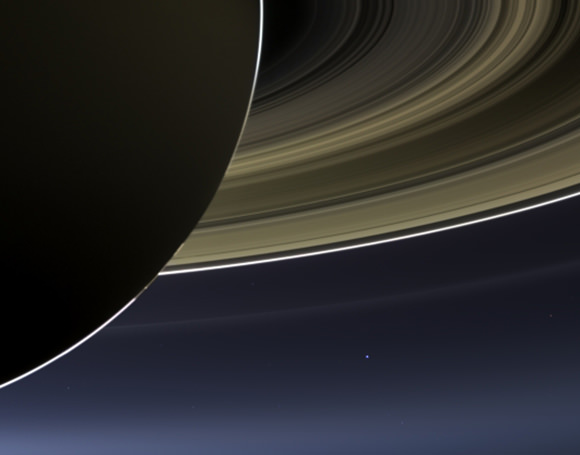

A few times during its mission, Cassini took a photo of home. There it is, that pale blue dot. We aren’t even a tiny speck in the cosmos. Among the stars, our own sun gets lost in the glare of greater, larger stars. But from Saturn, we shine, meekly, dimly, beautifully. I so value the perspective we gain from sending probes out far away. I love the things we learn about those far away places, because they make our home even more precious, if not to the cosmos, then certainly to us. If only we could realize, remember, and retain the knowledge that all way have in the cosmos is that pale blue dot, and each other.

Thanks, Cassini. I’m going to miss you.

© 2017, gar. All rights reserved.