The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power is a diverse, non-partisan group of individuals, united in anger and committed to direct action to end the AIDS crisis.

–ACT UP New York’s motto, recited at the start of each meeting.

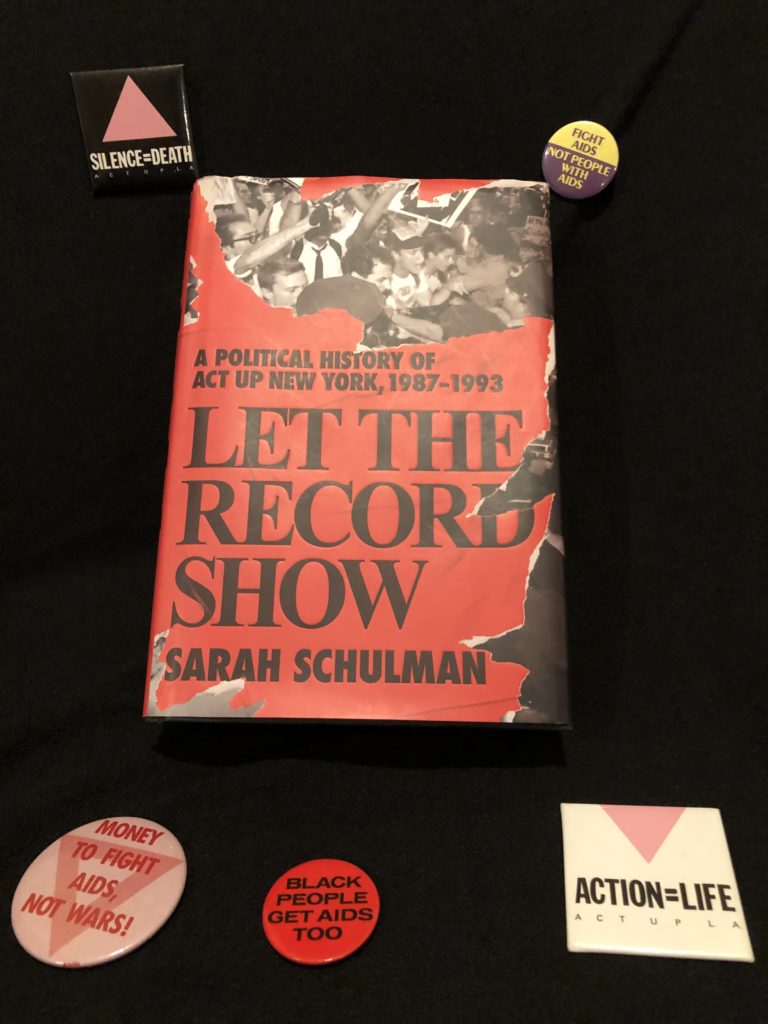

Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993 is a must-read book. Sarah Schulman—accomplished and prolific writer, playwright, and longtime activist—has written and meticulously pieced together a vital collection of stories, recollections, and remembrances about a turbulent and violent period of recent history, the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 90s. For those like myself—a Black gay man who came out during the age of AIDS—it is a reminder of what the community lived through. For others, it is a needed history lesson about a time when the US government allowed hundreds of thousands of people to get sick and die, and how that harsh reality led some to radical activism.

Sarah was active in ACT UP New York from 1987 to 1992. During that time, she participated “in countless actions, including Seize Control of the FDA (Food and Drug Administration), Stop the Church, and Storm the NIH (National Institutes of Health),” three of ACT UP New York’s best known actions. So some of the recollections in the book come from her own participation in the group’s work as a rank-and-file member who regularly attended the famous Monday night meetings. However, the backbone of the book comes from excerpts of long-form interviews of surviving ACT UP New York members.

In 2001, Sarah cofounded the ACT UP Oral History Project with Jim Hubbard to document and create an archival record of ACT UP’s history. By that time, the actions had largely faded away; the first “cocktails” of protease inhibitors had turned AIDS into a chronic disease and the immediacy that drove ACT UP, all of the ACT UP chapters nationally and internationally, had diminished. (NB: AIDS is still a crisis, still a killer, and still in need of a cure.)

Additionally, many who participated in ACT UP had moved on, or, as Sarah put it, “were licking their wounds and trying to rebuild their lives.” (Sarah herself would go on to cofound The Lesbian Avengers, another direction action group.) Because ACT UP rarely received comprehensive coverage in the media, the group needed a proper archival record of its activities. Otherwise, its true history would die along with its participants. Thus, Sarah and Jim conducted over 180 interviews between 2001 and 2018. Not all of the interviews are in the book, nor are each presented in their entirety. You can find the interviews, transcripts and video, on the Project’s website. The recordings are also available at the New York and San Francisco Public Libraries and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

By relying heavily on the interviews, Sarah brings together a highly diverse group of voices to tell the history of ACT UP. In my opinion, this is the book’s greatest strength. A truly diverse group of people formed ACT UP New York—women, African-Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, Latinx, Asian-Pacific Islanders, trans folks. White gay men certainly contributed to the group, but they were by no means the only voices. Importantly, diverse voices had diverse priorities, leading to a variety of actions. Including these voices helps to form a complete picture of the myriad of activities ACT UP carried out during the six years covered by the book.

For example, we learn that ACT UP New York had a campaign to find housing for HIV-positive Haitian refugees, a brave group of individuals who fled a dangerous and repressive regime in search of healthcare only to end up in detention at Guantánamo. Proof that its infamy predates the early 2000s by some decades.

ACT UP New York also created a needle exchange, setting an example that others would follow nationwide. Indeed, ACT UP East Bay, which started in my Oakland apartment in 1989, established a needle exchange in Berkeley (NEED, the Needle Exchange Emergency Distribution). It was fascinating to read how New York established theirs, since I participated in NEED’s creation over 30 years ago.

A section I found most informative, and infuriating, details the campaign to change the definition of AIDS to cover women. Without recognition of actually having AIDS, women lacked access to benefits and experimental drug trials. The Center for Disease Control defined AIDS by symptoms and ailments. Kaposi sarcoma, which led to purple skin lesions, was an early killer for many men who had HIV. Women, Sarah writes, did not often have this disease, but would often suffer from uncontrollable yeast infections or severe pelvic inflammatory disease. The CDC did not include these conditions in their definition of AIDS.

The campaign, ACT UP New York’s longest, lasted for four years. The opposition they encountered, both from the government and within ACT UP, was huge. It’s an outrageous example of how the medical establishment has continued to place women’s healthcare issues on the back-burner (if they’re on the stovetop at all).

The campaign’s slogan was “Women don’t get AIDS, we just die from it.” Significantly, while Sarah and Jim interviewed scores of HIV-positive men for the ACT UP Oral History Project, they did not get to interview any HIV-positive women. “By 2001, almost every HIV-positive woman in ACT UP New York, except one confirmed survivor, had died. And that woman did not want to be interviewed because her children’s spouses did not know that she was HIV-positive. She has since died.”

Sarah does not arrange this massive work in chronological order, stating that such an approach would be impossible and inaccurate. It is instead organized “by cohered themes and tropes.” This allows for better storytelling, and since the work relies heavily on oral histories, this is quite appropriate. Repetition of facts occurs naturally by this method, but that allows the reader to see a story from different angles.

Lots of names appear throughout the book, enough to make Dostoevsky blush. That’s OK. To tell ACT UP’s history properly, you need recognize the many who participated. It was a complex organization filled with people who otherwise would have had little or nothing to do with each other. But the sense of urgency created by all the illness and death that overtook their lives brought them together and motivated them to take actions that made significant progress in the fight against AIDS. Many lives have been positively affected by the work of ACT UP.

The book contains humor and hints at what a pick-up scene ACT UP New York meetings could be. But it also includes death, lots and lots and lots of death. One cannot understand ACT UP or the crisis that created it without confronting the fact that a lot of people died while campaigning to bring an end to the AIDS crisis. For that reason, the book weighs heavy, not just from its heft but also its content.

I had to pause many times while reading it, sometimes for a few days. Large books can sometimes intimidate me, but that wasn’t it. I recalled my own list of names and faces from ACT UPs on the West Coast: Connie Norman, Rick Turner, Steven Corbin, Mark Kostopoulos, Earl Baldock, John Iversen, other names I sadly cannot remember now, though I can still see their faces. They came to me while reading stories in the book. I paused and remembered them, their smiles and laughs, their fierceness and fighting spirits, the campaigns we did together—at County-USC Hospital in Los Angeles, at Highland Hospital in Oakland, in the streets of San Francisco.

We fought AIDS because it was killing us and society at large didn’t care. They didn’t care because they thought lesbians and gay men, people of color, trans people, and people who used IV drugs didn’t matter. They preferred our silence. As ACT UP taught us, Silence = Death.

Sarah Schulman’s book is an important triumph. She tells our story as only one of us could tell it. And her work counters the silence of a history ignored and therefore continues the fight of ACT UP to end the AIDS crisis.

© 2021, gar. All rights reserved.