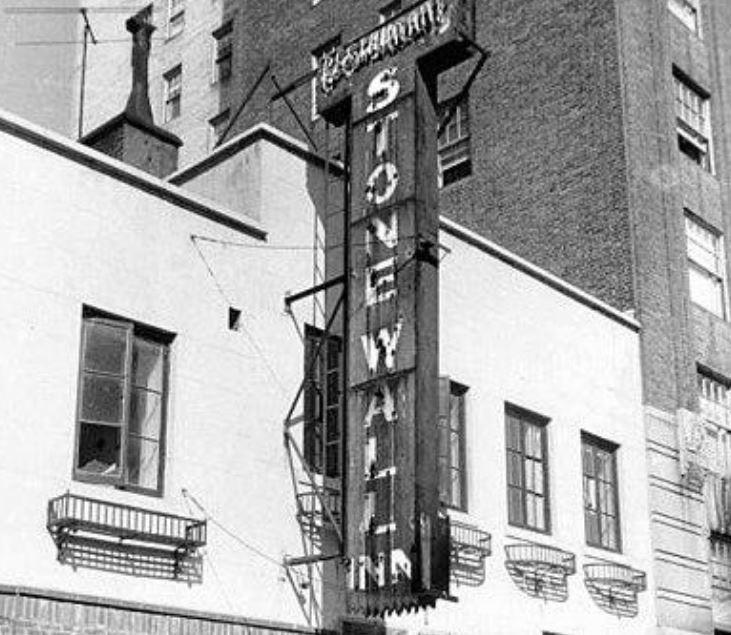

In 1988, I wrote an article for 10 Percent, the former LGBTQ news magazine at UCLA about Christopher Street West. The article also included a bit of history about the Stonewall Rebellion. As I had learned in my Civil Rights History classes, Stonewall did not just up and happen. Stonewall happened in the context of its era, a period of unprecedented rebellion against establishment norms that oppressed people of color, women, and queer folks. And, as with Watts and the Rodney King trial outcome, a series of tragedies led up to the night of June 28, 1969, when folks just couldn’t take it anymore.

While researching for the 10 Percent article, I learned about a tragic incident that occurred just weeks prior to Stonewall. A young man impaled himself on a fence while trying to escape a police raid on a bar. This tragedy has stayed with me ever since. Indeed, it inspired a scene in my novel Sin Against the Race.

Alfonso Berry, III, son of city councilman Ford Berry, was violently arrested by police at a needle exchange, a program his father disapproved of. In light of this tragedy, and at the instigation of Alfonso’s mother Eunice Berry, the city set up a Blue Ribbon Commission to investigate Alfonso’s arrest and beating. In this scene, Sammy Turner, the 60-something year-old store clerk, musician, and spiritual center of the novel, testifies before the Commission.

He picked a time when he knew Bill and Roy would be in school. Of the familiars, only Charlotte and Mrs. Berry attended.

“Mr. Turner, please feel free to tell us anything that might help us in our search for the truth.”

Sammy spoke in a slow tempo, like the slowest blues he had ever accompanied.

“By the time I arrived, Alfonso was already in the van. I saw when the officer yanked him out. I heard his head crack against the bumper, just like you can hear on the video. My heart stopped. And then they started beating on him.”

“Is that your voice on the video saying, quote, ‘Great fucking Dizzy! What the hell are they doing?’”

The panel sat patiently.

“Yes.”

“Did you hear any of the officers say anything prior to Mr. Berry being pulled out of the van?”

Another pause before he answered, “No.”

“Thank you, Mr. Turner. Is there anything else you would care to add?”

Sammy sat very still. Scattered coughs and fidgets punctured the silence.

“It was 1959. I was about 12. We lived on Carver Street next to one of the bars, The Owl. It was a two-story joint. I could see into the upstairs room from my bedroom window. I liked watching them dancing.” Remembrance of their tender faces touching while slow-dancing brought a glow briefly to his face. “It got raided one day, like so many bars did. Police started hassling people, hitting them. Some of the guys upstairs jumped out the window to get away. It was a good drop, but they risked it, ’cause if you got arrested, they printed your name in the paper.

“One guy didn’t make it. He impaled himself on a cast-iron fence post. I’ll never forget the way his face looked, tongue stuck out, eyes bulging. His arms and legs flailed for a bit before he went limp. They had to saw off the post to get him down. The newspapers reported the raid, printed names, but glossed over the man on the fence, calling it ‘a minor incident.’ Someone posted flyers telling the truth. I still have one. His name was Stevie Sampson. He loved to dance. Stevie survived four days with that pole stuck inside him before he died.

“I went into shock. Didn’t speak for a month, just played my drums. Finally, my dad come up to me and ask if I’d seen the police raid. I nodded my head and started crying. I couldn’t stop. I don’t think I’ve ever cried so much in my life. My dad took hold of me and said real soft, almost whispering, ‘Shhhh. That ain’t gonna happen to you. When you grown, they won’t be chasing folks out the bars no more. Know why? ’Cause you gonna see a better world, Son. A better world is waiting for you.’”

Mrs. Berry handed Charlotte a tissue behind Sammy’s back and used one herself.

“I’d had nightmares where I was the man on the fence with my eyes bulging and my tongue stuck out. I thought that was how my life would end. I don’t know how my dad knew, but he knew.

“For thirty-eight years, my store on Carver Street has been a safe space for young folks coming out into the life. That’s my contribution to make it better.”

Sammy felt his throat tighten. He squeezed shut his eyes and bowed his head slightly.

“But I couldn’t do nothing for Alfonso!” he shouted.

Mrs. Berry put her arm around him.

“This can’t happen again,” he said softly. “We can’t go backward. Not now. Not now. Not now. Not now.” His voice faded like the last track on an LP.

“Thank you, Mr. Turner,” Larkin said.

Sammy rose slowly. Chairman Larkin stood, as did the rest of the panel and the audience. All remained standing as Sammy and Charlotte left the room.

from Sin Against the Race, (c) 2017 Gar McVey-Russell

© 2019, gar. All rights reserved.