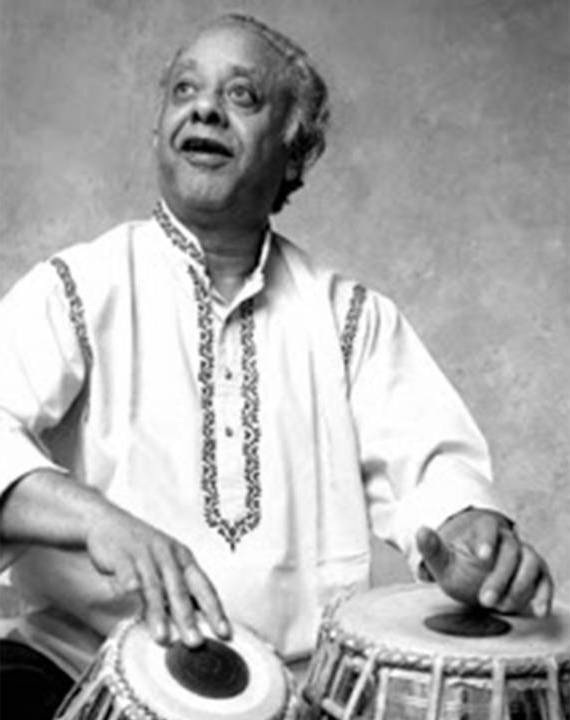

Two of my greatest musical idols were born on April 29. Duke Ellington, in 1899 and the doyen of the tabla, Ustad Alla Rakha in 1919. As the world celebrates the 100th anniversary of the birth of this musical colossus, who brought the tabla to a higher level of respect and dynamics, I reflect upon his music and how I eventually met him.

As a teenager in the late 70s and early 80s, I came to North Indian classical music from the source: the classical and devotional music programming on the General Overseas Service of All India Radio via shortwave. In Southern California, the station’s signal wasn’t always the best. However, some days I got lucky and reception would be clear enough for me to record the music off the air. I learned about the giants during this time. The Dagar Brothers. Ustad Vilayat Khan. Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. And of course Pandit Ravi Shankar and his longtime tabla accompanist Ustad Alla Rakha. My mother enthused about Ravi Shankar and Alla Rakha. She had seen performances on PBS.

Fast forward to UCLA. Its Ethnomusicology Department had not quite formed when I was a student in the 1980s, but the School of Music did offer ensemble classes in various musical traditions from around the world, including India. My dream of learning sitar came true under the tutelage of Prof. Nazir Jairazbhoy and his teaching assistants, Scott the first year and Richard (now Antar) the second.

But a funny thing happened at that first class. Prof. Jairazbhoy always had his students start on tabla. He taught us basic phrases. To his amazement, I had very good tone for a beginner, someone who had never touched the instrument. He kept saying “That’s incredible! Nobody ever does that!” I thought he was just flattering me. I only realized many, many years later what it was I had done so well. (For tabla folks: I played “na” and made it ring the first time I tried.)

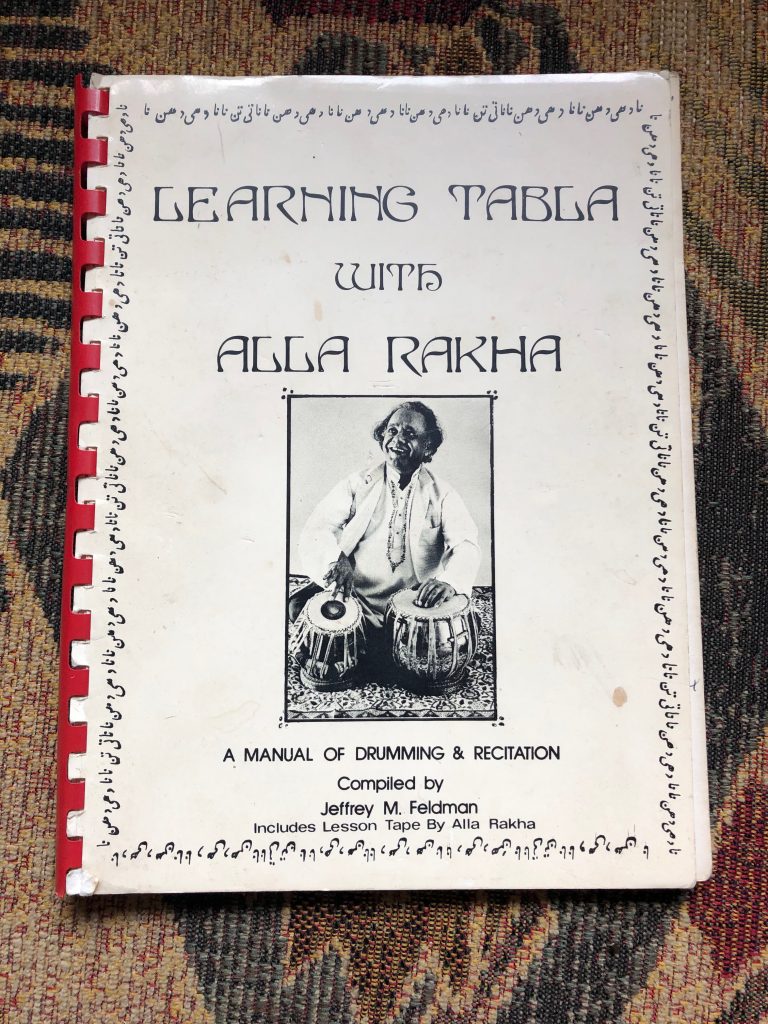

I played sitar in the class for a couple of years as well as take private lessons on the side. And then another funny thing happened. My sitar instructor went off to India to study sitar construction and insisted that I buy this pair of tabla from him. I did. Soon afterwards, I bought a book and cassette on how to play the drums called “Learning Tabla with Alla Rakha.” I went through the whole book in about a year, teaching myself the compositions, and I never turned back.

The first time I saw Ustad Alla Rakha, or Abbaji as he’s affectionately known, was in the fall of 1985. Soon after starting music studies at UCLA, I learned about The Music Circle, an Indian classical music performance society created by Ravi Shankar and his disciple Harihar Rao. The first concert for that season was none other than Pandit Ravi Shankar and Ustad Alla Rakha together. I was psyched.

These two masters toured internationally together for the better part of 40 years. They were part of the first wave of Indian classical musicians who brought the music to the West. Their performance at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, immortalized on CD and the famous movie, still gives me chills. Theirs was a unique partnership. You could hear rhythm in Pandit Shankar’s beautiful melodies and melody in Abbaji’s rhythms, so they complimented each other perfectly.

The concert was held at Herrick Chapel on the campus of Occidental College near Eagle Rock. Not a bad jaunt from South Central LA, where I lived with my family. Except I did not own a freeway legal vehicle at the time. I had a little Honda Aero 50 scooter. Therefore, I had to figure out a way of getting to Occidental College on surface streets. It took around 45 minutes and involved a lot of twists and turns. I called it a pilgrimage.

I melted under spell of their nonpareil playing. They bathed the chapel with beauty. After the first piece, Panditji’s son Shubho Shankar, joined them on sitar.

After intermission, Abbaji played a ten-minute solo in rupak-tal (7 beats). He shook the stage with some of his strokes, causing Panditji to raise his eyebrows as he counted out the rhythmic cycle. Abbaji also performed recitation, singing the composition he would then play. This tradition intrigued me on recordings but wowed me beyond words in person. When I got home that evening, I played a bit of tabla—softly so as not to disturb my parents in their bedroom adjacent—inspired by Abbaji’s playing and reciting. I studied his book all the harder after that magical night.

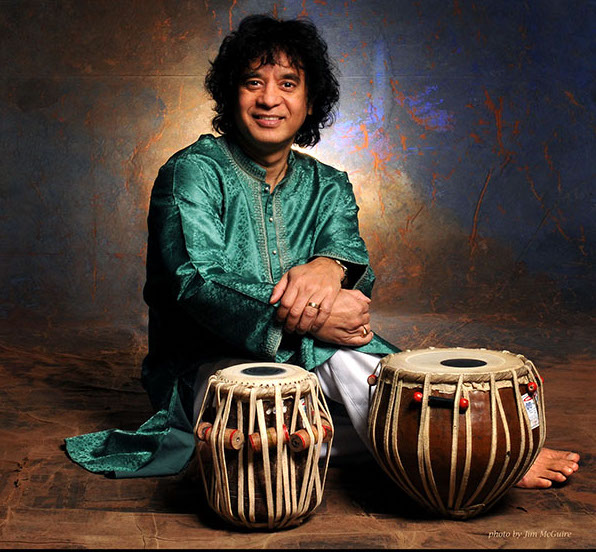

In 1987, I attended a concert in Little Tokyo, not a pilgrimage, but a short jaunt. It featured Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia on bansuri flute and Ustad Zakir Hussain, Abbaji’s son and disciple, on tabla. Both musicians dazzled the audience with a brilliant show, but Zakirji just floored me. So wowed was I, that overcame nervousness and sought out Zakirji after the show just to meet him. He was very friendly, setting my nerve at ease. As I related my amazement at his playing, he said nonchalantly “Just basic stuff.” He also mentioned that he taught summers in Berkeley.

Guess where I moved to two years later? To be sure, I had the Bay Area in my sights because I wanted to be around other black queer folks and to write. But the opportunity to study tabla with a great maestro and the son of my idol gave me additional motivation for relocating.

Studying with Zakirji summers in Berkeley and Marin was like a dream. We covered mountains of material, enough to last for decades. Indeed, there are compositions I still study and fiddle with these many years later. But I also learned from Zakirji’s example how to live the life of an artist and how to respect your art. These lessons also continue to inform me as a writer. I’m forever grateful for the time I spent studying with him.

Abbaji visited our summer classes twice during my summers in Zakirji’s classes. The second visit I’ll never forget. We met at the Julia Morgan center in a classroom-type space behind the famous auditorium. Zakirji led the first lesson and Abbaji sat to the side and watched us perform. I sat in the front row. “Let’s play the lesson,” Zakirji announced, then we launched into a kaida (theme) that I knew very well. It came from the “Learning Tabla with Alla Rakha” book. Zakirji would later tell us that it was the second kaida he learned from his father.

As we played along, going from one variation to the next, I glanced to my right and saw Abbaji, leaned forward, head tilted down slightly, staring at the front row. Nervously I looked forward and continued to play, but eventually my eyes drifted right again. Abbaji continued staring. Basically, I had 3000 years of Indian music history and tradition staring at my hands. No pressure! After a few moments of utter nervousness, my wandering eyes drifted toward Abbaji again, just in time to see him close his eyes, nod his head, and lean back. I felt like I had just past the most important test in my life.

None of us sat back and got comfortable for too long, however. When he came up to teach us, Abbaji gave us a piece filled with pauses and odd syncopations. After Abbaji demonstrated the kaida the first time, we turned and looked at Zakirji, who now sat where his father had, as if to say HUH???? Zakirji just shrugged and smiled. I heard in my head, “Basic stuff.”

Abbaji left us in February 2001. I learned of his passing two weeks after it had happened from the website of a friend. I wept, remembering not just his profound artistry but also his kind, gentle presence and spirit. A year later, Zakirji invited as many of us students who could attend to play at a concert in his father’s honor. How wonderful it was to play on stage with Ustad Zakirji and all my fellow students.

Ustad Alla Rakha remains an iconic artist, who will inspire tabla players and all musicians for many, many decades to come. I still reflect with a full heart how his life has enriched mine.

Happy 100th birthday, Abbaji!

© 2019 – 2023, gar. All rights reserved.