Dad was walking home from work one day when he suddenly started crying. He got home and Mom asked what was the matter. He couldn’t get the images of Vietnam out of his head. “How can we keep our boys away from that?” he said. Their boys, my older brothers, were coming close to the age where the draft could affect them in a most direct way. And my father couldn’t abide that.

Dad served in the US Army during the waning days of World War II. They shipped him off to Fort Devens in Massachusetts for basic training. Many moons later, I told him how my partner’s father, who came from Massachusetts, was sent to California for his basic training around that same time. Dad laughed. “They probably did that to keep us for deserting too easily,” he said.

Dad never talked much about his time in the military, not until his 70s. I remembered remarking to Mom, just months before she died, how interesting it was that Dad was opening up about this part of his life. She agreed, knowing more about that history than any of us did at that time.

Dad was about to get shipped to Europe, but then Germany surrendered. So he got sent to the Pacific theater. He mentioned a time when his unit was stationed on some island, getting shot at. His laidback demeanor did not convey any anxiety about the situation, though of course it couldn’t have been anything but tense. I can’t remember him telling that many combat stories. Perhaps he had few to tell. But his feelings about combat and war violence alone did not instill him with anxiety when thinking about his sons potentially going off to Vietnam. He had other dark experiences in the service, which probably explain why he only opened up about them after the passage of many years.

The US Army of the 1940s was segregated. Blacks had a limited number of career choices in the military, and nothing that could lead to good paying positions once the commission ended. My father became a quartermaster, the keeper of supplies. He talked once about a time when he was stationed somewhere in the South. I can’t remember which state, but at that time, it probably didn’t really matter. It was a cold, cold winter, and Dad issued himself, through all the proper channels, a nice, warm jacket. He wore it comfortably around the base, until a superior, a white man, saw him and asked where he got it. My dad told him, but the superior didn’t care. He wanted the jacket. Rather than start a ruckus, and risk likely physical harm, he gave him the jacket. My dad never received another. He told that story many times, and each instance tested the strength of his calm demeanor. 40 and 50 years later, it still bothered him to have been treated this way by a “fellow” soldier. One can only imagine what other slights he faced at that time. Fortunately, he did not have to serve in the South for too much longer after the jacket incident.

By the time of Vietnam, the US military had been integrated for close to 15 years. Though de jure segregation vanished, the attitudes that informed the old practices festered in the minds of many who entered service at that time. The Civil Rights movement brought the simmering feelings of a slighted people to Main Street all over America. The topic existed in everyone’s minds. Bigots who objected to uppity niggers demanding a place at the table fought along side the uppity themselves. My dad knew and dreaded, from his own experiences, that his sons would have had to face such people should they have been drafted, as if the bullets and bombs weren’t bad enough.

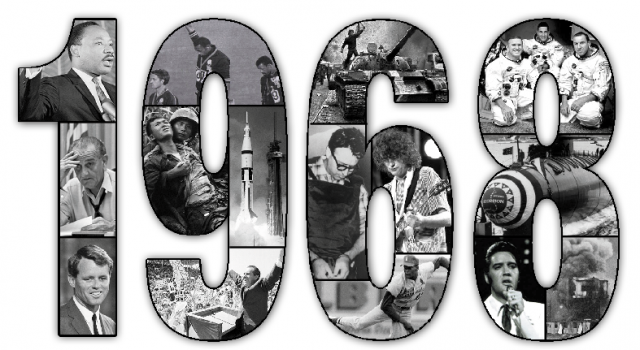

This family anecdote filtered through mind as I entered The 1968 Exhibit currently on display at the Oakland Museum of California (through August 19, 2012). I don’t know if my dad’s brake down occurred in 1968 or not, but there is no doubt that Vietnam was an ever-present image in everyone’s mind in that pivotal year. The exhibit captured this most brilliantly. When you walk into the space, you are immediately confronted with an actual Huey helicopter, one of the mainstays of the war. On one side, the Huey sat with its door open. Visitors could see inside the small cockpit and view first person testimonies of men who served projected on a cockpit chair.

On the other side of the Huey sat a low, cloth sofa and matching easy chair, a coffee table with displayed artifacts under glass, various wall hangings against tacky wallpaper, a console-cabinet filled with a set of World Book Encyclopedias, liquor, glasses, and knickknacks, and a television – all the trappings of a typical 1960s living room. The furniture actually looked strangely contemporary, likely because it’s all back in style again. I sat on the sofa and watched on the small screen TV Walter Cronkite wearing a helmet and reporting from the field. The loop then played part of his famous speech where he declared the best possible outcome of the Vietnam War was a stalemate. His blunt assessment helped to dissuade President Johnson from seeking reelection.

The Huey sat just to the right of the TV, a lurking giant. Even with the TV tuned to a different program, even with it turned off entirely, the Huey and its cockpit full of soldiers’ experiences remained fixed in the living rooms of 1968 America.

The 1968 Exhibit runs chronologically, with each month receiving a display area. But the timeline snakes through its space like a fickle river constantly changing its course. I got easily disoriented, an apt representation of this most disorienting year. Backwaters to the river exist as well in the form of displays highlighting fashions, technology, and TV programs of the year. Laugh-In started its first season in January 1968, and Star Trek its last nine months later, with the dreaded episode “Spock’s Brain.” My mother and I used to watch Laugh-In. At three years old, I didn’t begin to get all of the humor, but I remember liking Ernestine Tomlin, the overlord of the switchboard. My dad worked the swing shift and didn’t get home until late, so we’d often stay up and watch Red Skelton as well, sometimes eating crepes.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated some 6 days after my third birthday, so my tiny mind could not comprehend or form memories from that horrible day in American history. We lived with my Grandmother McVey, my mother’s mother, in those days. And while I can’t remember the King assassination, I do remember my grandmother having pictures of Dr. King and Malcolm X on the wall. The exhibit had on a very large screen the footage of Dr. King as he gave his final speech.

I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land.

His words commanded the space dedicated to April, and those of us passing by could not help but stop to listen, reflect, and still mourn.

When I think of 1968, the dual assassinations dominate my thoughts. Robert Kennedy clenched the California Democratic primary in early June. He spoke to his supporters at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, tired but happy, just moments before being fatally shot. A few days, or perhaps even a few hours before this dreadful moment, my mom took me to a rally where Senator Kennedy greeted folks, shaking hands and kissing babies. Rumor has it I may have fallen into the latter group. Again, I was too young to know about the tragedy as it happened, but I can picture now how my mother would have reacted, and how my father would have gone through lengths to console her, while at the same time trying to console himself.

Music helped everyone through the dark days, and music thrived in our household. Many, many years later, my mother and I commented time and again how wonderful the 60s had been for music, because everyone was into everything. And everything was so good. The jazz of Wayne Shorter, Lee Morgan, and Horace Silver flowed through our house along side the Beatles, the Stones, and the Who. And the classical music of India was in the house as well, represented by such pioneering ambassadors as Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, and Alla Rakha. Sadly, though, I could only find mention of the pop music 1968 offered at the exhibit, from Aretha Franklin to Frank Sinatra, with little mention of jazz or other musical offerings this year of plenty brought. But to be fair, the music of 1968, and the Sixties in general, would require an exhibition all of its own.

Near the November display sat an old-school voting machine, with the curtain, the little switches next to the candidates’ names, and the big lever one pulled back and forth to register a vote. I always wanted to use one of those machines, but if California ever had them, they were out and the punch cards were in by the time I started voting. The exhibit had the machine hooked up so that folks could vote for their candidate of choice, with the results displayed on a very 21st century flat screen monitor mounted above. The list of candidates included Robert Kennedy. Not surprisingly, given that this is the Bay Area, Kennedy was winning by a landslide, with 48% of the vote at the time I walked through.

My first-hand memories of 1968 are precious few, as already noted. However, the events of that year, culturally and politically, continue to affect us some 44 years later. Indeed, we share some of issues with that time. We still have unpopular wars which produce protests and divide households. But without a universal draft, and without the same type of coverage the Vietnam War received, the unmanned drone does not reside in the living room the way its predecessor the Huey did. Protestors against wars and social injustices have social media today, but are still informed by tactics used in 1968, whether they know it or not.

For me, however, to think of 1968 is to think of the might have beens, and the unanswerable questions they produce. What if Dr. King had lived beyond 1968, a time when his focused moved beyond Civil Rights for African Americans and towards economic and global issues? What if Kennedy had lived? Would he have won the presidency? What impact on the war would that have had? Would my father’s fears about his growing sons being drafted have been allayed?

© 2012 – 2018, gar. All rights reserved.

Dear Gar, What an excellent essay! Your writing is so exquisite. One can’t helped but to be taken in by the impressive and insightful way you convey your story. You write in such a commanding fashion. I wanted to read more! I was taken back to my own age of seventeen and the feelings of turmoil, anger and confusion. This was a rather transformative time for many of us. The question of what if they lived, for both Dr. King and Robert Kennedy, continues to live within me too. Thank you for sharing this part of our history which we will never forget!

Thank you, Philip, for the kind remarks. We have to remember this history!