This story could be called a love letter to the Duke Ellington Orchestra. I wrote it around the time I fell head over heels for all things Ellington and started listening to his music 23 out of 24 hours in the day — a practice I continue to the present time. I immersed myself in all things Ellington to learn as much about what Mahalia Jackson once called a “sacred institution.” And that’s when I learned about Billy Strayhorn. Mr. Strayhorn was the Maestro’s composition partner from about 1939 to 1967, when Billy died of cancer at the age of 51. But I was moved and awed when I learned that Billy was gay and that he was, for his era, fairly open about it. That is to say, he didn’t go to great lengths to hide it. He wore no beards.

So this got me to thinking about being black and gay in the 30s and 40s, and that was the inspiration for The Swing Shift. This story was originally published in the magazine Mobius in 1999.

The fantasy started that night, in the shades of black he wore and the shades of tan that made up our skin as we stood together in the wings overlooking the orchestra. I stood behind him and allowed my hand to brush against his, allowed my breath to circulate a bit near his left ear before escaping to add to the humid thickness above our heads. We survived intermission, serving the musicians in the green room, and now they reappeared refreshed on stage. Our quality time resumed as we listened to the glorious music in our secluded corner, a treat beyond category. That night we swung with royalty.

Our boss made sure our tuxedos fit just right, no slacking, no slouching, no cuffs drooping over the hands like a shaggy-haired dog. Reggie’s tux fit ever so right that night. Not so much as a loose thread hung from his jacket, as it contoured every muscle of his shoulders. In the front, the white shirt obeyed the mounds on his chest and betrayed them through the fabric. Reggie’s legs and ass filled out his pants just right to cause a sensation inside of me; they were loose enough to be of comfort to him, but tight enough to make me wish my fingers took the place of the stitching that held them together. Reggie did not conk his hair that night, but left the small, tight tuft of hair on his head in a natural state. We fidgeted silently with each other. Such motions had to be cloaked in silence.

I lived for those Saturdays together. Beneath the humid stuffiness of the night’s air, beneath the canapé of notes produced by the band, beneath the wings of the curtain – draped like the giant wings of a black butterfly to protect us – we glowed on each other the kind of light that could only shine from those who beckoned tender acknowledgment, of being and presence. We saw only each other in the glow, as we truly appeared. Such a joyously verisimilar sight of two men in each other’s gaze could only exist in these darkened corners. We tried the movie houses, like others of our kind, but found they did not work for us. Even without much light, our darkened skin as it touched each other seemed to reveal too much of our intimacy to outsiders, in the flickering light of the projection on the screen. No, here, backstage at the swing club where we both worked, it was safer here. And of course there was always the music.

On the stage, the piano player, in his subdued, regal splendor, pounded out a methodical beat. The orchestra caught the cue and obeyed. Reggie and I knew the piece well and had debated its meaning many times. I’m sure our interpretations differed substantially from those of the pale skinned audience in the club. They probably heard a dark jungle full of Negroid foreboding, a tantalizing fantasy in the same way a Halloween story can scare the senses without causing any permanent discomfort; for them the story would end eventually, and all would return to normal. That’s not what we heard. We heard in the muted trumpets a muted man who’s scream couldn’t be softer or more painful. He wore a face not entirely his own to appease those with delicate sensibilities as he dutifully executed demeaning chores on their behalf. “And even if we play the game,” Reggie said, “we still ain’t safe. They can take it all away like that <<snap>>.”

Reggie spoke of one mask, though really we wore two. One came with birth, the other grew out of necessity. One shielded us from the harshness of those with fairer skin, that we may appear docile and harmless and not a threat to them. My favorite version of this mask was always the happy watermelon man, with the natty hair, thick red lips, and wide grin shining over his food of choice. The image was so unlike me or those I knew that it always struck me as ironically humorous, through its grotesque facade. And I saw him everywhere, a constant reminder of how I should look, or how they saw me, regardless of how I saw myself. But our other mask defied easy description. How can you describe the invisible? True, there is always the image of the limp-wristed sissy, fussing over hair or nails – but that mask only worked if you worked in entertainment. There it became acceptable. Worn anywhere else and it would land you in the hospital’s emergency ward, or morgue. So the other mask, then, was no mask at all. Invisible, it rendered you invisible and thus less of a threat to others, and less a danger to yourself. To be the man you knew you had to be was your best protection.

Wearing masks all the time can give you a bad disposition. And Reggie had that rage within him. He tried to teach himself to alchemize the poison he felt inside into a defiant spirit that damned the rules as we’d come to learn them. It was in such a moment that Reggie ignored protocol and our surroundings and kissed me backstage, square on the lips. I had goaded him into it, unwittingly. One night I kept asking him ‘Do you have a girlfriend’ and ‘What’s she like.’ I asked as a defense mechanism. I just knew he had a girl somewhere he called his honey. He was too perfect-looking, too sweet, too kind not to have one. Every hombre I ever find myself attracted to ends up having a girlfriend, and then I have to endure listening to him go on and on about her, while I pretended to know the experience of having one. And I always smiled, sickly sweet like my watermelon friend, so not to betray my unrequited heart. It didn’t take but a few weeks working at the club before I had fallen for Reggie, and his tall, lean magnificence. So I kept asking the questions, just to get it all out of the way. ‘Let my heart sink now, quickly,’ I kept saying to myself, ‘Let it die now.’ Finally Reggie, who acted like he didn’t hear my questions, turned to me and took me square by the shoulders and kissed me full on the lips, backstage in the open, where anyone could have seen. I nearly fainted in his arms. When Reggie released me, he said ‘How could you ask such questions, when I’ve been trying to put the sugar on you for nearly a month now? I was beginning to think I was wrong about you.’ I could only smile sheepishly. It’s hard to see clearly sometimes with these damned masks on, and sometimes I would forget to take them off.

As the dirge played on stage, I grabbed a hold of Reggie’s coattails. He reached back and caressed my tightened hands with his subtle fingertips. I relaxed my grasp and began fingering the inside of his palm. The piece had its lighter moments, when it sounded like the muted man had something he could call his own. Maybe a small, but comfortable place, maybe some records, maybe a sweetheart he visited from time to time. Maybe the music suggested an impromptu visit, and the two lovers sat on the couch together, holding hands.

Reggie’s fingers slipped between mine and we pulled a bit closer. My breath warmed the back of his neck now. I could feel his eyes close as his sigh reverberated through his chest into mine. This was our moment, in the shadows, away from peering eyes. We would see each other outside the job at the club, and on other nights besides Saturday, but always in settings common to others. So we wore the masks to present to the world faces not our own to appease those with delicate sensibilities as we dutifully avoided any hints of intimacy. Even with such precautions and predispositions, the very air about us threatened to betray us as more than just ‘two guys’ jiving together. Backstage at work, with no one else around, and the orchestra playing, we could allow our fingers to slip in close proximity of each other, from time to time.

Ah, the wah-wah played now. The music got a little sassy. Maybe the muted man got horny, and made a pass at his honey. Behind the closed draperies of the apartment, he could risk such behavior. We aren’t supposed to be sexual, not even with our own.

I dreamed of his lips touching mine at times of our mutual choosing, and wondered under what circumstances could such a thing happen. We both lived at home, with our respective families. The ice creams parlors and park benches that openly invited other lovers to enjoy their offerings were needless to say quite off limits to the two of us. Sure, Reggie allowed his lips to moisten mine in a wonderful display of carpe diem, but such impulses came rarely. The built-in inhibitions and dreads, beaten into us from an early age, kept such acts on the endangered species list.

I told Reggie this point of the piece sounded like the man ran into some jive-talking friend; you know the type, the one that’s always running some kind of game that would bring him instant wealth. Reggie nodded. Maybe the jive-friend did craps or ran odds at the race track. Maybe he had a head for numbers, like the mathematician he should have been, had it not been for that inane mask he had to wear all the time, with seeds stuck between his teeth.

Reggie and I should open our own club. He has an excellent business sense and can lay the charm on anyone. And I can work wonders in a kitchen. We’d serve some of the best food you’d find anywhere. And the place should have the grandest dance floor alive, hopping with all sorts of folks. But I would want this place to cater mostly to our folks, a sea of black men dancing cummerbund to cummerbund. The music would hang over our heads like a night’s fog. Our shoes would glide over the hardwood floor, polished to perfection, reflecting our beauty like a lake in the woods. Our band would sail our guests for hours on end, and at the right moment, Reggie and I would enter, descending from a grand staircase, dripping with jewelry, our clothes neatly draped over our bodies; hand in hand we’d come down those stairs to the applause of our guests for that evening, so happy to have this place they could call their own. So thankful to us for making it possible. And Reggie and I would glide onto our reflections on the dance floor and walk on water.

The sassy wah-wah trumpet sounded again, and the end of this particular piece grew nearer. I could feel Reggie’s hand take mine. He always said this part made him nervous. For him it announced the end of the dream, the end of the walk, and the announcement of Reality, in all its guises. As the wah-wah pleaded for mercy, The Man would thunder back ‘No!’ And so it would go, till the Man had heard enough. As we listened in the wings we heard the notes form a Chopinian dirge to tell the story of how another one of our own had fallen. Another had marched to his own predestined doom. Maybe he got to work late for the first time and was fired on the spot. Maybe he played the horses wrong, and his bookie got sick of him. Maybe his man left him for some woman because the pressure of juggling two masks proved too much.

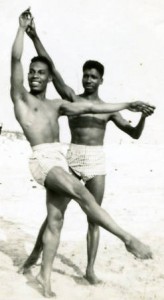

One day we took the train out to the beach, and we walked along the shore during the early morning hours when no one else was there. I told Reggie about my Great Idea that we should open a club of our own, with the flowing staircase, and how we would descend from it ever evening to the applause of our patrons, like a royal couple arriving at the ball. He smacked his tongue against his teeth and asked me how many rocks did I have in my head to think of that. And I said to him, ‘Well, why not? We don’t have to live every day like we are marching to our doom. Maybe doomsday will never come for us. Why not have a club for brothers in the life to dance in, and drink and party in, and love each other in? What would be the reason for not wanting such a thing,’ I said to him. He told me that it just could never happen, and that we shouldn’t waste our time thinking of things that could never happen. He said being a Negro was bad enough, but that even other Negroes wouldn’t put up with a couple of ‘out’ fairies running a club for other fairies. He seemed kinda defensive. I could hear the words squeeze through the tightness of his voice. It wasn’t him speaking, but the poison coming through. It strangled his usual fluid diction into drips of words that impacted my head like a water torture. I did not need to hear this, not from him. I heard reality daily, even when all voice boxes stilled. I countered with a softer tone, almost a plea. ‘Don’t burst my bubble,’ I said, ‘I know I can’t have much, but I can have my dreams.’ I told him how I would never give those up, not for the Man or anyone else, not even him. He took my hand, and held his head down. Our arms began to swing as we walked across that beach together, now hand in hand. Then he said, ‘Well, you just go on dreaming. And if I tell you not to, just tell me to shut up. You know how I get sometimes.’ I took his hand up to my lips and kissed it lightly on the back. He smiled his pretty smile, and I felt better. It wasn’t that he thought my dream totally nuts; it just hit too close to home to what he really wanted, and felt we could never have. He wanted the two of us to live together in the same apartment and to sleep in the same bed every night and we could cook our meals together and live like a real couple. I wanted this, too. ‘We’ll have ours one day, baby,’ I said to him. He squeezed my hand. “I know,” he said.

The depressing notes of the last piece let loose to some high wheeling chords and bouncing rhythms. We felt the change in the air and started to wiggle. Reggie started to move his ass back and forth in our corner, and I joined him from behind with my hands on his hips. We rocked it in rhythm. Then we froze suddenly, like deer caught in a headlamp. We both heard a sound, like tapping or footsteps. We looked around and saw only a small figure in dark clothing. He looked black like us and it looked like he wore some dark rimmed glasses, but it was hard to tell as he stood in a shadow. I let go of Reggie immediately, but the little man didn’t stay too long. He seemed to look in our general direction, then he turned and walked towards the green room. A collective sigh overtook us both, accompanied by the usual nervous giggle. We escaped doom once more. Afterwards, we thought it time we headed for the green room ourselves to set up the after show refreshments: plenty of liquor, and lots of Coca-Cola for the piano player.

As usual, it was slow in the green room after the show. When all the applause and encores faded, some of the guys did come back for a final drink, but most seemed pretty tired and just packed their stuff and left. Except for the piano player, who sat at the piano in the back with the little guy we saw backstage as we jive-danced. He did wear dark rimmed glasses, and he had a big nose, and short hair. He had a serious look on his face as they went over the charts together. But he had a serenity about him, too, that dampened whatever sharp edges his face displayed. And he dressed very smartly in dark pants, with matching shoes, a vest, and a light colored shirt; he wore a large ring on one finger with a dark stone.

“You know who he is?” I asked Reggie.

He just shook his head no.

They didn’t stay too long. After a while, the piano player got up and headed for the door, but not before thanking Reggie and me for serving them refreshments. He gave us $10 each. We both couldn’t stop grinning – $10! He smiled graciously as we fell over each other thanking him. His music had been a bonus enough. His friend sat at the piano for a while, then slowly got up and walked in our general direction.

“Did you boys make this food?” he asked.

“No, sir,” I said.

“Do you want to take any with you? We’re about to put it all away,” Reggie said.

“No, thank you,” he said with a smile.

Then he walked quietly out the green room. We started our closing routine after he left.

Sweeping the dance floor I started thinking again about owning a club. I looked around and imagined all the little decorations and additions I would make to this room, to make it as grand as possible. Floor to ceiling windows framed with Mr. Macy’s finest draperies would be a requisite, plus complementary, not matching, tablecloths. And all the men would dress so fine in their evening wear of black and white. I didn’t realize it but I had been turning around in a circle with the broom in one hand while composing all this grandness. Reggie came up to me with that look on his face, pulled in a smirk.

“You like dancing with the broom now?” he said.

I told him I had been thinking about the club I wished we had. He nodded. He told me he had finished in the back. I nodded. Our job for the night was about done, save for turning out the lights and locking the backdoor after we left. Mr. Redheffer had paid us already and he trusted us to close everything up right, for some reason. Most wouldn’t, but he was different. Reggie took a hold of the broom just below my hand. His eyes looked big and sad, and I avoided contact with them. He dreaded this moment as much as I did. Once through the backdoor we would have to conform as required, with hands at our sides or better still in our pockets. When we part, smiles would have to do, and nothing more. We would have to place the masks on our faces again, and hide our true selves, till we could do better. I loved our Saturdays together, even if it meant a lot of work, just because it meant we were together.

Then Reggie turned his head, and I felt my stomach jump into my throat. We both heard it, and wondered where it came from. We looked towards the stage. It was the piano. The little man whom we saw back stage, with the dark-rimmed glasses and fine suit, sat in a shadow at the piano and started to play. Our instincts told us to walk away. And Reggie had started to move towards a side door. But then the man held a chord with one hand, and beckoned with the other like a conductor signaling his players to do it, make it happen. We stopped our retreat. We could see him waving his hand; he also seemed to be saying “Dance!” Then he turned his attention back to the piano. His playing filled the room with a lush life, intimate, blue, reflective. We became entranced. Who was he, I kept thinking to myself. The room took on a totally different life with his playing. The mugginess lifted. A calm presence entered the room. He touched the dynamic and the light in his playing, songs which we had never heard. They were not swing numbers but more like ballads, without words. I could see the tall windows now, with burgundy curtains from Mr. Macy’s store. I could see the tables lined up against the wall with golden tablecloths draped carefully over their sides. I saw the men in their best suits, drinking and talking together. And the music brought us all together, provided by this one man, small and quiet, though intense and sincere, as he played his instrument.

I bent at the knees to set the broom down on the floor. Reggie looked at me as I rose.

“May I have this dance?” I said.

He looked at me, but held his tongue from the poison it may have spat out, and took my hand instead. We glided on the floor as the music played. We glided on water, as our cheeks came close together. We glided around in circles of our choosing, our masks no where to be seen. The music gently sailed us from one corner to the next, always in contact, always touching, holding, breathing together. The man with the glasses did not stop playing, but seemed to sail lithely from one melody to another like one tableau melting into the next. I pecked at bit at Reggie’s ear, and he then blew into mine. The air turned moist as his tongue danced into my lobes. My fingers danced along his back, down his spine, and to his ass. No reflection glowed from this old, dull floor, but still we became kings of the ball.

“Are they clapping for us yet, baby?” Reggie said.

“Oh yes, they are,” I said.

When we came to close the broom, a beautiful crescendo flowered from the piano, and then a final, inspired note sounded. And it ended. We looked in his direction and saw he had been joined on the bench by someone else, a much taller fellow, dressed equally fine, and he had his arm around our piano player. They sat and talked for a moment, then both rose to leave. I rushed up to the edge of the stage. My eyes looked squarely at the one who had filled my dream of a lifetime, if only for a few moments.

“Thank you,” I said.

He grinned and bowed his head in our direction, then took his companion by the arm and they both whisked out the side entrance.

Reggie looked at me and I at him. Did we just share a collective daydream? Did he just play for us, for our sole enjoyment so we could dance cummerbund to cummerbund, then leave with his male partner?

“Do you think they live together?” I said.

“Wouldn’t that be something?” Reggie said hopefully, “Wouldn’t that just be something?”

We walked off the dance floor and back towards the stage. Reggie hit the main switch. Off went the lights and another evening together. I pulled the curtains to. He came up behind me and I turned. He took the back of my head, and laid a warm, wet, sweet lipped kiss on me. I took his behind and pressed him closer to me. The curtains, like the wings of a black butterfly, shielded us; though the lush tones from our piano player still reverberated in the hall and in our hearts, as we kissed.

© 2011, gar. All rights reserved.

This is so poignant. I dig the representations and variations of the masks…timely then (for the set time-period) and now. The descriptions are sensitive, yet unapologetic. I’m really feeling it. Thanks.

BTW,

Happy New Year!!!!

Happy New Year back at ya, bb!

I don’t even know where to begin. I don’t even know where to begin. Handsomely and hauntingly beautful, dude.